|

LIBERIA'S FIRST CIVIL WAR, 1989-1997

|

The seeds of Liberia's first civil war can be traced back to divisions between the native population and descendants of freed slaves from America and the West Indies who settled in Liberia from the 1800s. Although only constituting 5 per cent of the population, the Americo-Liberian freed slaves, in alliance with Africans liberated from slave ships

bound for the Americas (the “Congos”), dominated political, social and economic life. They failed to grant equal treatment, freedom and political inclusion to the native tribes of the interior and monopolised power for 133 years before their last president, William Tolbert, was overthrown on 12 April 1980.

|

|

William Tolbert

|

A. The Prelude

|

The immediate antecedents of civil war in Liberia can, however, be found in the excesses of the rule of Samuel Kanyon Doe, a 28-year old Master Sergeant (Staff Sergeant) in the Liberian army, who overthrew the Americo-Liberian dominance. There was popular support for Doe and his People's Redemption Council (PRC) from the majority population of native Liberians since this was the first time a native led the country since independence in 1847. But Doe's popularity disappeared rapidly as his rule began to resemble that of his predecessors. Like them, Doe created a governmental system that benefited one ethnic

group, in this case the Krahns, who made up only 4 per cent of the population. The ethnic groups in Liberia are Bassa, Belle, Dei, Gbandi, Gio, Gola, Grebo, Kpelle, Kissi, Krahns, Kru, Loma, Mandingos, Mano Mende, Sapo, and Vai.

|

|

Samuel Doe

|

|

INSERT-1: (TLP) DOE ENTERS THE ARENA

"After the euphoric and popular reaction to the emergence of the military upon the Liberian political scene, the People's Redemption Council [PRC], headed by Samuel Kanyon Doe, failed to fulfil initial post-coup d'état promises of establishing a 'new society'. Instead of implementing policies of inclusion, political procedures were initiated which established patterns of ethnic seclusion. One result of this restrictive official strategy was the formation of a broad-based coalition of indigenous Liberians and foreign insurgents under the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) which aspired to depose Liberia's Second Republic".

|

Initially Doe surrounded himself with some Americo-Liberian elite, but they soon became his adversaries as he slowly tried to dispense with them. But Doe's biggest mistake was to make himself an enemy of the native people and of young left wing “progressive leaders, who had been important to his rise to power. Some of the latter were from settler families or were natives who had received elite educations. They were members of the Movement of Justice in Africa (MOJA) and the Progressive Alliance of Liberia

(PAL), two groups originally established in the 1970s to pressure the Tolbert government.

|

INSERT-2: (TLP) DOE & THE USA

"In 1980, Samuel Doe, a 28-year-old indigenous Krahn, seized power and killed William Tolbert, the last Americo-Liberian president. When Doe took over, he knew nothing about how to run a government. He was illiterate, and he had little education. He learned quickly how to make himself rich and how to shore up political support. He demolished the True Whig party that had controlled Liberia's politics for more than a hundred years, but he did not replace it with any other coherent form of government. He was good at developing allies. He learned English, Liberia's official language, by studying videotapes of Ronald Reagan who invited him to the White House and called him "Chairman Moe". During the culmination of the cold war in the 1980s, Doe courted the Reagan-era American Republicans and received millions of dollars of American aid. The American aid established Voice of America transmitters and maintained the Robertsfield airport which the U.S. used to transport weapons to Angola.".

|

MOJA and PAL preached radical and quasi Marxist ideology, though MOJA was principally a pan-African movement and had branches in Ghana and the Gambia. Both groups were formed by young intellectuals. In the lead up to the 1980 coup, MOJA had established night schools known as the Barrack Union to politicise the army and encourage it to overthrow the Tolbert government. Amos Sawyer, later to be head of the first interim government during the civil war in 1990, ran the classes.

|

Some from these groups formed part of his government and competed for his grace and favour, often falling out and betraying one another in an attempt to gain more power. A notable character was Charles Taylor, who had been chairman of the student movement, the Union of Liberian Association in the Americas (ULAA), while studying in the U.S. during the 1970s. Taylor became director of the General Services Agency, a government procurement body, soon after Doe's coup.

|

|

Charles Taylor

|

|

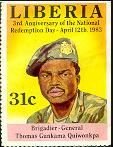

As Doe consolidated his power he came to rely less and less on the “progressives”. Hence, more than the Americo-Liberian elite, the “progressives” were instrumental in his downfall. Several attempts to remove Doe were foiled during his nine-year rule. The first serious challenge came in 1983 when he announced his ambitions to become a civilian president under a new constitution after pressure to return Liberia to democratic rule. This opened a split between Doe and others of his junta, including Doe's close ally, General Thomas Quiwonkpa, commander of the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) and a Gio from Nimba County.

|

|

Thomas Quiwonkpa

|

There are thirteen counties in Liberia: Bong, Bomi, Grand Bassa, Grand Cape Mount, Grand Gedeh, Grand Kru, Lofa, Margibi, Maryland, Monsterrado (which includes the capital, Monrovia), Nimba, Rivercess, and Sinoe.

|

INSERT-3: (TLP) ORIGIN OF THE NPFL

"There is some controversy as to when the NPFL was formed and who its original leaders were. One school of thought locates the formation of the movement under the former Army Chief of Staff, Thomas Quiwonkpa in early 1985, and stresses that the few escapees among the motley group of dissidents who invaded Liberia in November 1985 formed the original clique around which the broader-based opposition movement, NPFL, coalesced. Yet another school of thought locates the formation wholly under Charles Taylor, as the primus motor in modelling the exiled Liberian opposition organisations into the required structure and transforming it into an efficient fighting force. Irrespective of which of the two schools of thought is correct, it can be asserted that the patronage system, at least, played a prominent role in the initial appointment of Charles Taylor as the Director General of the General Service Agency (GSA). There is an element of association, therefore, between Quiwonkpa's loss of power in 1983 and the subsequent repression and retrenchment of those associated or related to him. This led to Charles Taylor's eventual escape to the United States amid official accusations of embezzlement, a charge which was rescinded at the height of the civil war".

|

Quiwonkpa, who was instrumental in Doe's rise to power, feared that Doe's elevation to the

presidency would limit his own power and that of the military, but also seal Krahn dominance. Quiwonkpa sensed he was losing power in the PRC when Doe offered him the post of secretary-general, which would have removed him from the army. Quiwonkpa refused and, fearing for his life, went into exile. His close associates and protégés followed him, including Prince Johnson, his military-aide-de-camp, and Charles Taylor. Some who fled to Côte d'Ivoire, including Samuel Dokie, a Mano man from Nimba County who was to become an ally and then an enemy of Charles Taylor during the civil war, led a raid on Nimba on

21 November 1983 that attacked government offices and killed several people. Many of the

raiders who had either escaped capture or were pardoned left the country and prepared for the next coup.

Doe's victory following the 15 October 1985 rigged elections sealed the hatred of the natives, in particular the people of Nimba County. Many believed that Jackson F. Doe (no relation to the president) of the Liberian Action Party (LAP) had won. Jackson Doe was the son of a Gio from Nimba, who had been recruited by Quiwonkpa to work in the government. From 1985, after he consolidated his power, President Doe plunged Liberia into violence as he attacked his political opponents. As his legitimacy eroded, Doe

depended increasingly on the Krahn and on the Mandingo community, a minority Muslim ethnic

group with extensive commercial and trading links in the region.

|

Disillusionment led Quiwonkpa and others linked to the “progressives”, including Joe Wylie (later to become a member of the LURD), to launch a coup on 12 November 1985. Its failure resulted in a brutal campaign of repression against the Gio and Mano peoples in Nimba County, Quiwomkpa's strongest supporters, by Doe's Krahn-dominated Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL). The people of Nimba County nursed a deep resentment towards Doe's regime. It was, therefore, not surprising that the civil war was launched on Christmas Eve 1989

in Nimba County and that the core fighters of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) rebels were mainly Gio and Mano.

|

|

Joe Wylie

|

The Christmas Eve War

Charles Taylor is not a Gio, nor is he from Nimba County, but he was a protégé of Quiwonkpa. Taylor was related by marriage to Quiwonkpa. Taylor is a child of inter-marriage between a native (his mother, a Gola) and a Congo, thus making him “all things to all men”. the U.S. in 1983. While there he was accused by the Doe government of embezzling U.S.$900,000. Taylor was imprisoned pending extradition, but escaped fifteen

months later and returned to West Africa. Taylor was able to tap into a largely disaffected national and exiled population to build a strong network of forces in his campaign to challenge Doe and later claim Liberia for himself. Many Liberians beyond Nimba

County were dissatisfied with Doe and wanted him removed. Exiled Americo-Liberians living in Côte d'Ivoire saw Taylor as a way back to power following their overthrow in 1980, thinking him practically one of their own. For the people of Nimba County, many also exiled in Côte d'Ivoire, Taylor's campaign allowed them to inflict revenge on the Krahns and Mandingos.

At least 150 fighters trained in Libya and Burkina Faso crossed from Côte d'Ivoire into Nimba County, attacking government officials and Armed Forces of Liberia soldiers. Internal rivalry and splits within the National Patriotic Front of Liberia emerged from the start as some rank and file soldiers from Nimba offered loyalty to their commanders like Prince Johnson rather than Taylor. Johnson left the National Patriotic Front of

Liberia to launch the Independent National Patriotic Front (INPFL) as early as January 1990. He captured President Doe and video recorded his murder on 9 September 1990 to show everyone that he and not Taylor was responsible for the end of the regime and therefore successor to the presidency. Further splits surfaced within the National Patriotic Front of Liberia in 1994, when another breakaway group, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia Central Revolutionary Council (NPFL-CRC), was formed. Key founders of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, such as Tom Woewiyu, Sam Dokie and Laveli Supuwood (now

a member of the LURD) fell out with Taylor over the objectives and direction of the movement.

|

INSERT-4: (TLP) ROLE OF THE AMERICO-LIBERIANS

"An important initial patronage factor whose role is regularly overlooked in the analysis of patronage patterns that affect the armed coalition is the role of Americo-Liberians. In the latter stages of the military interregnum, the PRC attempted to co-opt sections of influential Americo-Liberian groups into government, while others preferred to remain in exile, outside the reach of the PRC and the Second Republic. Charles Taylor, already well known in the United States as an effective and persuasive organiser, managed to win extensive support among exiled Americo-Liberians, who funded the coalition to an estimated tune of $1 million. This claim stands in sharp contradistinction to William Reno who claims that 'Taylor begun financing his operations with the plunder and sale of machinery from the abandoned German-operated Bong Iron Ore Company'. John Chipman's evaluation of NPFL economic policies contradicts Reno's pillage theory. To Chipman, NPFL's ability to manage the economic potentials of Greater Liberia can be explained as resulting from the credibility of management strategies of the areas under NPFL control, and as a consequence gained the confidence of foreign companies in dealing with the NPFL. Stephen Riley, on the other hand, asserts that, the NPFL fueled its war effort by continuing the export trade ... with timber still going to the European community (FRance)'. Appearing before the Subcommittee on Africa in the U.S. House of Representatives, Ambassador William Twaddell, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, stated that Charles Taylor had as much as USD 75 million a year from the sale of diamonds, timber products, iron ore and rubber to markets in Belgium, France and Malaysia. Analysing the extent to which Americo-Liberian support was possible for the NPFL, Ellis on the other hand contends that 'most Americo-Liberians valued their rights of entry to the USA too highly to risk dabbling with anti-American governments'. In attaching excessive relevance to Americo-Liberian relations with the United States, and thus hesitant to take on board a Libyan financed and trained NPFL, Ellis overlooks collective Americo-Liberian abhorrence with the Monrovia regime, and thus primed to underwrite movements aimed at bringing about societal transformation. Characteristic of embedded disparities in Liberian society, indigenous Africans provided the bulk of the fighting troops while the Americo-Liberians contributed financial and leadership support".

|

|

INSERT-5: (TLP) THE GHANA DIMENSION

"The nature and character of Ghanaian patronage and later dissociation from Charles Taylor during his search for refuge and support should be situated in the context of: (I) the internal political circumstances in Ghana; (II) the nature of Ghana's relations with Liberia; and (III) Ghana's search for regional allies. In December 1981, the democratically elected government of Ghana was overthrown by a radical army group calling itself the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) under the leadership of Jerry Rawlings. In immediate post-1981 coup statements, the new government stated its desire to chart a radical revolutionary course, both internally and externally. The first major action undertaken by the PNDC (which has an interest for the present work) was to re-establish diplomatic relations with Libya which had been suspended by the previous government because of official anxiety concerning 'Libya'(s) international terrorist campaign(s)' (January 1992). Initial responses from ECOWAS leaders were cautious but varied as a result of the violent nature of Rawlings' earlier four-month rule in June-October 1979.

During the early 1980's, Liberia had consistently accused the Ghanaian government of subversion. Liberia's initial reaction to Ghana's declaration of a 'Holy war' was the immediate recall of its Ambassador from Accra in protest against the resumption of diplomatic ties with Libya (West Africa, 25 January, 1982). Ghana-Liberia relations continued to deteriorate until Ghana's chargé d'affaires was eventually declared persona non grata in November 1983. This resulted in his eventual expulsion for 'activities incompatible with his diplomatic status' (November 1983). Liberia subsequently accused Ghana of backing an external invasion of the country in November 1985. It is in this context of Ghanaian-Liberian relations between 1982-1985, that Ghana's extension of patronage of Taylor's uprising should be situated. However, despite the facts surrounding these relations it is asserted that:

'Ghana was one of the few supporters of the Doe coup in 1980. While it is probable that Rawlings was drawn to Doe because of their mutual alienation by other West African leaders, there is little doubt that their initial relationship benefitted from the revolutionary ideas which they both espoused. By the mid-1980's, however, a major ideological rift had occurred between both revolutionaries.'

There is a fundamental historical implausibility in this argument. Placing Ghana-Liberia relations in a historical context highlights the confusion surrounding the above point. Ghana's 'cautious optimism', to changes in Liberia was modified after the execution of TWP leaders, to reflect the general trend of hostility shown by regional states towards the PRC government. This resulted in endorsing both ECOWAS and the Organization of African Unity - OAU - criticism of the brutality of the take-over, and the initiation of ECOWAS' punitive measures embracing three sets of interrelated gestures. First, the Foreign Minister, G. Baccus Matthews was prevented from participating in the Extraordinary OAU Economic Summit in Lagos, Nigeria, in April 1980. Subsequently, the new Defence Minister was not invited to a meeting of ECOWAS Defence Ministers in May 1980. The height of collective regional abhorrence towards the new regime was reserved for the President. Samuel Doe was refused participation in ECOWAS' Heads of States and Government summit in Lomé, Togo, in May 1980.

By the time Ghana's own revolution occurred on 31 December 1981, a conservative turn of events leading to major reorientations in foreign policy had occurred in Liberia. The Libyan People's Bureau was closed and the Soviet Union told to reduce its diplomatic staff. Liberia ultimately re-affirmed its traditional ties to the US. This led to an internal power struggle in the cabinet in which the radical faction of the PRC was purged. Liberia was subsequently selected by the U.S. as one of twelve international bastions against the spread of communism and was to receive support from a special security assistance programme.

Ghana's decision to support Charles Taylor, then, apart from the regime's stated democratic revolutionary credentials, can probably be inferred from the nature of relations between Ghana and Liberia. According to the influential weekly, West Africa, '... The present Ghana government has no love for ... Doe (August 1990). During the 1980's Doe perceived Ghana as unfriendly, frequently accusing Ghana of supporting 'dissidents' seeking to overthrow his regime'. It can be argued that, though the initial Liberian responses to Ghanaian changes were much more severe than the general regional response, they reflected widespread regional indignation with events in Ghana.

Byron Tarr and Prince Acquaah asserted that, though Charles Taylor's initial feelers to the Ghanaian government were positively received, this altered over time, resulting in Taylor being incarcerated twice in Ghana. Diverse explanations have been offered. Though at this point, the essence of these imprisonments was lost on all major actors in this fledging struggle to lead the exiled opposition movement to resist the Second Republic, it is crucial for the later arguments and the subsequent escalations in the Liberian conflict that it comprehends the dynamics of this seemingly unimportant episode. The incidents are also particularly important in several contexts. They reflect: (I) the nature of regional politics and alliances in addition to the initial introduction of the fledging Liberian opposition to Libya; and (II) these incidents' influence on the character of ECOWAS' original response to the accelerating conflict.

With respect to Ghanaian rationales for breaking with Taylor: by 1987, Taylor had obviously become a political and security liability as a result of the increasingly attentive Ghanaian youth audience fascinated by the revolutionary charisma and romanticism of Charles Taylor's rhetoric. Situating such youthful political consciousness within the context of the internal political climate in Ghana in 1987, it can be argued that Taylor, in the eyes of the Ghanaian authorities, had become a political and security liability. According to a defected Ghanaian intelligence officer:

'there were a number of Ghanaian dissidents [willing to] fight alongside Taylor in Liberia. Rawlings was worried that if Taylor triumphed, Liberia would be used to launch armed attacks against Ghana.' (New African, April 1991)

There is the plausibility of yet a more substantive motivation for Ghana's change of strategy. Ghana's revolutionary rhetoric on the regional level and close alliance with Libya and Burkina Faso had led to consistent regional accusations against both Ghana and Burkina Faso for supporting regional destabilization efforts generally, and especially against Togo (West Africa, July 1987). Ghana's increasingly weak and isolated position in terms of regional criticism for harbouring dissidents and consistent condemnation had, by 1987, made her a regional pariah state. During an incident concerning alleged Ghanaian complicity in an invasion of Togo, Nigeria, Togo's close regional ally during this period condemned Ghana as the 'scourge of international terrorism' (West Africa, July 1987). It can, therefore, not be denied that with increasing regional isolation, internal disturbances and an economy on the verge of bankruptcy, and in the middle of sensitive negotiations with international financial institutions, supporting an invasion of another regional state would have further isolated Ghana".

|

|

INSERT-6: (TLP) THE BURKINABE FACTOR

"In 1987 Taylor approached the Embassy of Burkina Faso in Accra and requested assistance to overthrow Doe ... Madam Mamouna Quattara, a client of Captain Blaise Compoare, received Taylor's written proposal.' Ghana chose to release Taylor into the custody of Blaise Compoare. Soon after these incidents, the Burkinabe Head of State, Thomas Sankara, was assassinated. Accordingly, 'Compoare, now leader of Burkina Faso, introduced Taylor to the Libyans'. Another perspective relates to Taylor's Accra sojourn and search for international backing. The late Thomas Sankara, leader of Burkina Faso ... secured Charles Taylor's release from Ghana. He was then deported and left for Burkina Faso where he stayed before going to Libya'.

The close relations between Ghana and Burkina Faso can be situated in the post-1982 period when Burkinabe infatuation with Ghana and Libya increased. In an increasingly unstable West African region in the early 1980's, it is believed that the conservative leaders of Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, Niger, and Togo were incensed by the Burkinabe Prime Minister's revolutionary rhetoric and close contacts with Ghana and Libya. Thus, through their French and Ivorien contacts, it was ensured that the Prime Minster was removed from power.

A rapid change of fortune occurred when Sankarists took over power in August 1983. Thomas Sankara's government, characterized by pan-Africanist fervour and revolutionary rhetoric, alienated West African leaders who found Burkinabe and Ghanaian brands of radical pan-Africanism untimely. Most regional leaders believed that Ghana and Burkina Faso were instrumental in attempts to overthrow their governments. Other perspectives can explain the apparently hostile reaction of regional leaders to both Ghana and Burkina Faso. This was a period of increasing political consciousness among the youth in these two countries and of the spectre of its possible domino effect in the region, there was regional irritation over the politicization of the youth.

Any analysis of the nature of international support for the NPFL should also consider the role of two other West African countries, apart from Burkina Faso and Ghana, in the initial organizing stages - Côte d'Ivoire and Libya. In addition, there was a motley group of individual West African nationals who came primarily from Burkina Faso, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea and Sierra Leone. Understanding the rationales for Burkinabe patronage for the NPFL especially in the post-Sankara period is best understood through the prism of internal and regional politics. Apart from the earlier mentioned initial contact to the Libyans, the Burkinabes provided training facilities and troops estimated at 400 men, a position justified by Burkinabe leaders as 'moral duty' and 'moral support' extended to the NPFL. A conceivable logic behind dispensing political and military patronage to the NPFL, could be NPFL complicity in the power struggles between Sankara and Compoare and an active NPFL role in the subsequent death of Sankara".

|

|

INSERT-7: (TLP) THE LIBYAN & IVORIAN ELEMENTS

"A critical analysis is also important for any appreciation of the dynamics of the unholy alliance comprising Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire and Libya for the NPFL insurgence. This has been characterized as 'a particularly strange alliance of forces'. There has been controversy concerning the entré of Libya into this typical West African crisis. The Libyan factor in the Liberian crisis has been interpreted by arguing that Blaise Campaore, who had close affiliation like his predecessor, Sankara, with the revolutionary government of Libya, influenced the Ghanaian authorities to release Taylor into his guardianship. This stands in conspicuous contradiction to the explanations presented by Prince Eric Acquaah, who claims that the late Thomas Sankara, leader of Burkina Faso, was instrumental in securing the release of Charles Taylor from jail in Ghana.

The political foci of Ivorian motivation for supporting the NPFL is more varied and complex. The essence of such extensive patronage as encompassing personal, economic, ideological and military factors were critical to the Ivorien decision to provide sanctuary, weapons, conduit, finance and diplomatic support for the NPFL. One of the most critical factors for Ivorian extension of patronage to the NPFL could have been the Ivorian economic crisis resulting from the fall in commodity prices. By the early 1980's, a severe drop in commodity prices affecting especially cocoa and coffee created an urban crisis which contributed to the growth of nationalist perceptions critical of Burkinabé migrants. The collapse of coffee prices was particularly critical for the Ivorian economy and national psyche. The resultant aftermath was a financial crisis in which growers did not earn enough to cover labour costs. This indirectly led to the rise of xenophobia against Burkinabés. The combination of these two issues: the contemporaneous fall in commodity prices and the increasing sense of xenophobia generated conditions of apprehension for Burkinabe men. In a desperate act of survival and realpolitik, both states chose to support the NPFL in the hope of diverting domestic attention from the critical internal crises faced by both governments.

Another crucial factor which is normally overlooked in the analysis of Ivorien support for the NPFL is closely related to what has been described as 'French appetite for African territory' resulting from Paris' willingness to exercise military power to procure land in the previous century. French strategy for territorial possession resulted in the acquisition of parts of Maryland County in 1892, followed by more land around the Makona river in 1907. Thus, when Liberian indigens finally took over power in 1980, there were expectations for Liberia to pursue efforts at reclaiming territory lost in the previous century. The PRC's initial response was an understandable reluctance to pursue a narrow irredentist policy of reclaiming lost indigenous territory. This position was to change, however, as the internal situation in Liberia worsened. In a Liberia where the Second Republic faced increasing internal and international criticism over the failed re-civilization programme, added to the worsening economic and human rights conditions, there was a desire among policy makers to find an excuse to divert public attention and arouse renewed sympathy and support for the PRC by appealing to nationalist sentiments. Desperate to arouse nationalist backing for government's policies, the cabinet met to discuss 'modalities of militarily recapturing territories lost to France. The focus was on the Ivory Coast'.

Thus, to reduce a possible incidence of fighting a protracted border war at a time when Ivorien commodity prices had crashed, in the political and geo-strategic calculations of the Côte d'Ivoire government, backing an insurgency sympathetic to Ivorian aspirations to maintain their colonially inherited boundaries was found a much more prudent approach than dealing with the machinations of an increasingly erratic Liberian Second Republic. Despite the above analysis, it has been argued that, 'Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire had no direct stakes in the outcome of the power struggle in Liberia".

|

In seven years of fighting other warring factions that emerged were headed by prominent political and military figures who had risen through the ranks of the “progressive movements' and were either closely allied to Doe, for example George Boley and Alhaji Kromah of the United Liberation Movement for Democracy in Liberia (ULIMO), or fell out with Taylor. Former fighters from ULIMO are now part of today's LURD insurgency. ULIMO, founded in May 1991, was mainly a merger of Doe loyalists, predominantly from the

Krahn-based ethnic group. One of its groups, the Liberian Peace Council (LPC), was headed by George Boley, former advisor to President Doe. A second group, the Liberian United Defence Force, was headed by an ex-functionary in the Doe government, General Albert Karpeh. A third group, the Movement for the Redemption of Liberian Moslems (MRLM), was founded in February 1990 by Doe's former Minister for Information, Alhaji Kromah, in Guinea. A fourth group contained elements of Doe's army who had fled to Sierra Leone. By 1994, however, internal struggles within the movement over the allocation of posts in the Transitional Government led to a spilt and the formation of a mostly Krahn wing, led

by Roosevelt Johnson (ULIMO-J), and a predominantly Mandingo faction, under Alhaji

Kromah (ULIMO-K).

At the start of the conflict there was an assumption that the United States would intervene in what is often regarded as an American protectorate. The countries had close ties reflected through long established economic, political, military, social and

cultural links and the fact that Liberia was long governed by descendants from nineteenth-century American slaves. But the arrival of U.S. Marines on 5 August 1990 was to rescue U.S. nationals and not to intervene directly in the conflict. Many Liberians consider that the U.S. is partly to blame for Liberia's fate by having prolonged Doe's survival during the Cold War. Doe made Liberia strategically useful by hosting U.S. intelligence

and satellite networks, the Omega Navigational System, and a VOA relay station. Hence,

Washington provided Doe U.S.$500 million in military and economic assistance while

overlooking his brutal leadership. Liberia's misfortune was that its civil war coincided with the end of the Cold War; which overnight cost the country its strategic utility.

As the conflict intensified, the absence of U.S. intervention led to increasing pressure for West African states under the auspices of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to act. The U.S. encouraged this, and on 25 August 1990, 3,000 troops from the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Observer Group (ECOMOG) landed in Monrovia. The intervention was controversial from the start because various

member states (e.g. Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Nigeria and Sierra Leone) used Liberia's warring factions to advance their particular or regional economic and political aims. The Liberian crisis exposed old rivalries and differences between French and English-speaking West African states, the consequences which are still being felt in Guinea and Sierra Leone.

|

INSERT-8: (TLP) TAYLOR SUPPORTERS

"There is some contention, though, to the extent to which explicit support from certain ECOWAS member states was procured, and the processes through which such patronage was either extended or withdrawn. During his sojourn in West Africa after Charles Taylor's 'escape' from the United States in 1984, Ghana, in consequence of its own declared 'democratic revolution', granted him residence during the initial phase of recruitment and planning. Ghanaian support for Charles Taylor has never been officially confirmed. It is, however, known that Taylor's request was favourably received by Ghana, and subsequently, an approach was made to Libya for financial and material assistance and a pipeline for military hardware and finance was opened. Burkina Faso similarly extended facilities for training, banking, armaments transfer and a detachment of troops to support Charles Taylor's uprising. Côte d'Ivoire, an otherwise conservative regional power, extended patronage in terms of political and diplomatic facilities, and facilitated the transportation of arms and the encampment of troops prior to the invasion. A non-regional actor, Libya, in consequence of its stated desire to get a foothold in West Africa, willingly extended training, finance and weapons to Charles Taylor. How do we explain this extensive patronage for a regional uprising?".

|

The UN, which initially appeared overstretched by other peacekeeping demands, finally stepped in to assist ECOWAS. However, it was not just other commitments but also African reluctance that had prevented the global body from playing an immediate role when conflict broke out. Taylor did, however, make several requests to the UN, primarily to neutralise ECOMOG, and particularly Nigeria. The UN finally intervened when the

Security Council passed Resolution 788 in November 1992, following the second assault by

the National Patriotic Front of Liberia on Monrovia. The resolution supported an ECOWAS

call for an arms embargo on all warring factions and requested that the Secretary-General dispatch a Special Representative to evaluate the situation. The Security Council established an Observer Mission in Liberia (UNOMIL) in July 1993. It was to be unarmed, while ECOMOG provided security. This was the first joint peacekeeping mission undertaken by the UN in co-operation with a regional group.

Many atrocities occurred over seven years of fighting. Within weeks the people of Nimba

County marked out the Mandingos for their collaboration with the Doe regime, while the

Krahn-based Armed Forces of Liberia targeted Gio and Mano supporters of Taylor in and around Monrovia. In many ways, within the wider contest for leadership, the war was about the revenge of one particular native group against another. As the war continued, attacks became more widespread and indiscriminate. For example, a wide range of human rights abuses, including massacres, torture, and kidnapping, took place during the two major

battles for Monrovia, first in 1990 when the National Patriotic Front of Liberia fought against the Armed Forces of Liberia and Prince Johnson's INPFL. The National Patriotic Front of Liberia assault on Monrovia in October 1992, codename “Operation Octopus” in which five American nuns were killed, was marked by treachery as Taylor’s forces struck while peace negotiations were taking place. Most people conclude that all sides

committed atrocities.

In the UN inquiry following the June 1993 Harbel massacre, which claimed the lives of 600 Liberians, mainly displaced men, women, children and elderly, the Armed Forces of Liberia were singled out. The Carter Camp Massacre: Results of an investigation by the panel of inquiry appointed by the Secretary-General into the massacres near Harbel, Liberia, on the night of June 5-6 1993, United Nations, New York, 10 September 1993. In the total course of the conflict, over half the country's population of 2.6 million was displaced, internally or externally. Estimates of deaths, some using different standards

(e.g., directly or indirectly related to the fighting), vary from 60,000 to 200,000.

Political assassinations were also frequent on all sides, but predominantly within the National Patriotic Front of Liberia camp as Taylor sought to eliminate potential rivals. Close allies such as Elmer Johnson, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia chief military strategist, and Moses Duopu, secretary-general of the National Patriotic Front of

Liberia, were ordered executed by Taylor in June 1990. Those more popular than him, such as Jackson Doe and Cooper Teah, a famous battle front commander who was close to Taylor's

mentor, Thomas Quiwonkpa, were killed in 1990 and 1992, respectively. Taylor's method of

eliminating rivals was sufficient warning of how he would rule once in power.

Nine peace agreements and at least thirteen cease-fire arrangements illustrated the lack of commitment to peace. None involved any real political solutions or dialogue. Taylor negotiated only when he was under pressure. A string of meaningless national and international conferences and three successive interim and transitional governments by April 1996 provided further evidence of how uninterested all sides were in negotiating peace. Liberia was held hostage to competition between power hungry individuals who had been struggling for the presidency since the 1970s and 1980s.

When the war started, it was a battle between two men for control - Doe and Taylor, but as it continued, it soon became clear that it had become, effectively, a war between Taylor and Nigeria's military leader, President Babangida. From the start of its intervention, ECOMOG was used to pursue Nigeria's objective of preventing Taylor

from winning. When the Nigerian-led ECOMOG force blocked Taylor's attempt to take over the

capital, he carved out his own fiefdom, calling it the National Patriotic Reconstruction Assembly Government (NPRAG), an alternative administration based in Gbarnga, Bong County,

from where he controlled half the country and styled himself president. With the exception of the shipping industry, Taylor was able to deny the official Interim Government, set up in 1990, access to most income. The Interim Government controlled the capital and its port. Taylor ran a successful business during the war through commercial links. One example was iron ore mining with the British firm African Mining Consortium Ltd. The Ivorian capital, Abidjan was a meeting point for Taylor's financiers, who traded

for weapons, communications facilities and military training. Other warring factions, such as ULIMO, traded in diamonds illicitly mined in Sierra Leone.

When ECOMOG troops finally attacked Taylor's administration in Gbargna in 1994, he realised that his only way to claim the presidency was to negotiate directly with Nigeria. Taylor's fortune was that Babangida was no longer in office. A new leader with fewer personal ties to Liberia, President Sani Abacha, provided Taylor with an

opportunity to reach a rapprochement. On 19 August 1995 the leaders of the main warring

factions signed a peace agreement (the ninth), the Abuja I Peace Accord, in that Nigerian city. There were nine peace accords in total: the Bamako Cease-fire, November 1990, the Banjul Joint Statement, December 1990, Lomé Agreement, February 1991 the Yamoussoukro I-IV Accords of June-October 1991, the Cotonou Accord, 25 July 1993; the Akosombo Agreement,

12 September 1994; the Accra Clarification, 21 December 1994; the Abuja Accord, 26 August 1995; and the Supplement to the Abuja Accord, 17 August 1996.

After more than five years of fighting in the bush, Taylor finally arrived in Monrovia with the full support of Nigeria. Under the Abuja Accord, Taylor and other warlords were given a stake in a new Council of State, “in effect a collective presidency in which

the principle factions were represented”. The Council system allowed each faction leader to run parts of the state. Ministries were divided up, posts were negotiated, and each leader became a vice-president, thus bringing each warlord closer to his goal of claiming the presidency. What it effectively did was to allow warlords to enter Monrovia and

further criminalise an already criminalised state.

But the main warlord, Charles Taylor, did not want to share the state, and he pursued a tactic of collaboration with the aim of destroying or eliminating his rivals from the Council and claiming the presidency. In December 1995, when the final stage of the disarmament process was to end, Taylor struck a deal with his rival, Roosevelt

Johnson, for ULIMO-J forces to attack rather than disarm and evacuate the diamonds fields in the west of the country to ECOMOG. Taylor guaranteed Johnson support for this operation. ECOMOG was surprised by Johnson's attack primarily because he had been a key ally to it in the war. During the attack a murder occurred that Taylor used as justification to remove Johnson from the Council. In what is now known as the “6

September 1996 incident”, fighting erupted when the police moved to arrest Johnson on charges of murder. The police were supported by the ULIMO-K and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia.

As fighting continued, National Patriotic Front of Liberia fighters gained the upper hand. With growing concerns that Taylor could take Monrovia militarily, it is alleged that the Nigeria and the U.S. provided other warring factions, including ULIMO-J, with weapons to attack the National Patriotic Front of Liberia. At least 2,000-3,000

people died in the fighting, and Nigeria was embarrassed by Taylor's attempt to foil another peace process that it had created. But once again Nigeria had blocked Taylor’s attempt to claim Monrovia and the presidency as his own. Nigeria then bolstered its peacekeeping force, reviewed the mission and attempted another peace deal. Taylor

finally came to realise that with Nigeria in Monrovia, he could not easily overrun the capital. To succeed, he would need Nigeria on his side, so he cooperated on another peace agreement. Thus on 17 August 1996, the Supplement to the Abuja Accord was signed. This provided for a cease-fire to be implemented by 31 August 1996; disarmament and demobilisation to be completed by 31 January 1997; and elections to be held on 30

May 1997, later postponed to 19 July 1997. Charles Taylor went on to win the presidency in a landslide victory, with 83 per cent of the vote, against twelve other candidates.

|